Critical Corner: Hoods Landing, Life on a Loop

In this edition of Critical Corner, a review of a fantastic debut novel and a moving show about aged care.

“All happy families are alike, unhappy families are unhappy in their own way” is something Anton Chekhov wrote, although probably in Russian. We love a good family drama, and the way it holds up a slightly smudged, definitely cracked, mirror to our own. It’s also a remarkably hard genre to get exactly right, which is why so few of them properly stand the test of time, and instead fall back onto library shelves and op shelf books, too closely tied to one style or too unmoored to be specific.

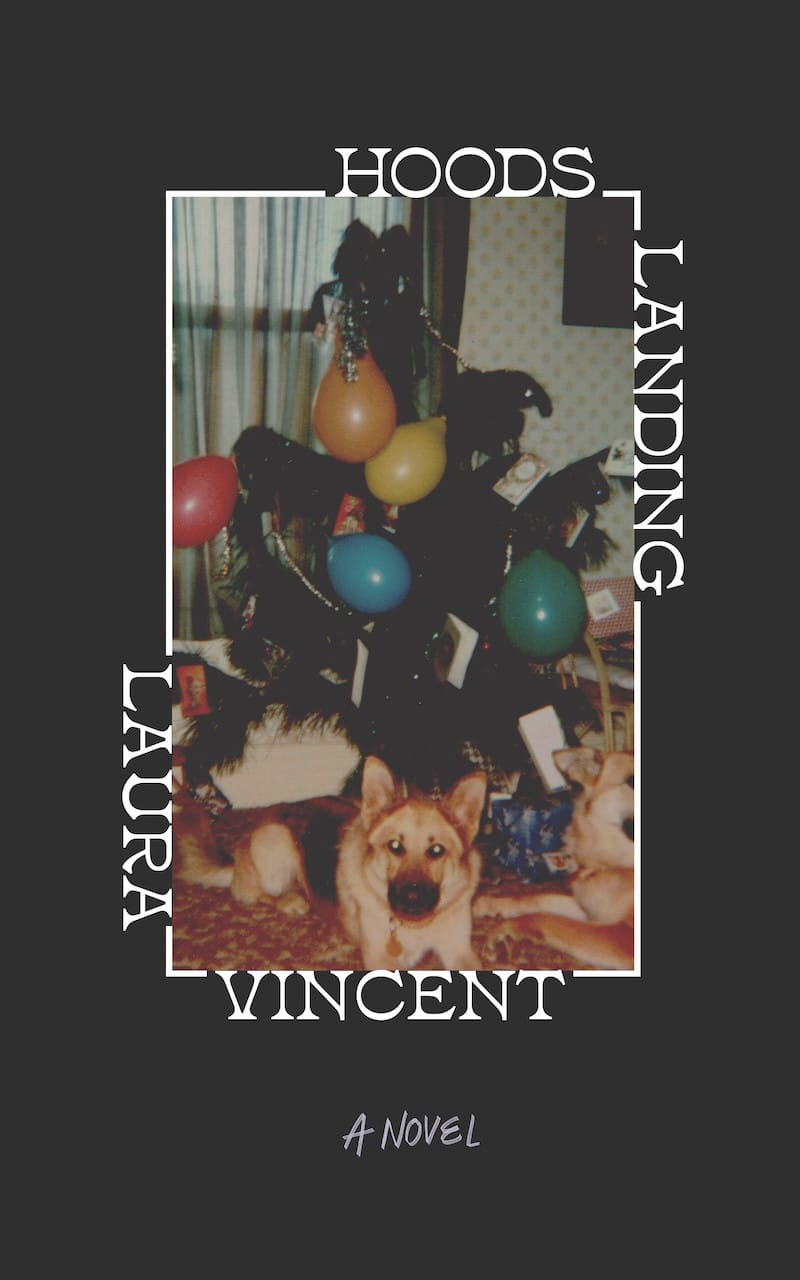

With Hoods Landing, we’ve got a contender to rise far beyond the chaff. This debut novel by Laura Vincent follows the extended Gordon whanau as they gather somewhere south of Auckland for matriarch Bufty’s birthday, with all of their various amounts of baggage and enthusiasm that comes with any mass family gathering. It’s a tremendous family drama; operatic in scope, intimately detailed, deeply funny, and so real it scratches a familiar itch.

It is Vincent’s voice that is the winner here. She writes with the cadence of a narrator – my brain has dreamcast about five tremendous New Zealand actors who could read the audiobook – in the corner of a bar, reciting the stories she knows so well. She tosses off observations that pinpoint a character’s entire life in just a few words, such as these assessments: “They called him a quiet man. It was more that his family was very loud.” and “Life was a combat sport for Judy.” Her novel is stacked full of these observations, but they never cage her characters, instead she turns the light on them from a different angle, to see a different side.

The author also proves herself an admirable technician. As a playwright who can delegate the job of placing characters in a room to a director, I deeply admire that the rooms that Vincent places her formidable cast in never feel crowded or confused. If you gave me a floorplan, I’m sure I could place every member of the Gordon whanau in the many locations they are sprawled in across the books; who sits where, how they move, who gets the drinks and cleans up the dishes. The author’s sense of place is so attuned, and lived-in, that she can pick a single detail to stand in for an entire house, and the entirety of that household’s existence. When a character late in the book declares a favouritism for Chicken Crimpys, I felt that deeply. We all know a person who loves their Chicken Crimpys, and we love them despite (or perhaps because, gasp) of that.

On a scene by scene level, Hoods Landing is one of the most intricately crafted debut novels I’ve read recently. Vincent plows through the narrative in fourth gear, not quite speeding but not quite meandering through, to get us home by Christmas, to misuse a metaphor. Scenes that are so full of conversation that they could be plays never feel stagy, and she knows exactly the right moment to zoom out and lightly touch on a character trait, or another observation, before throwing us back into the fray. It’s an impressive ability, and one that you expect from someone who has been around the prose block a few times, not someone making their debut.

The beauty of a book that is full of so much death – short interludes focussed on characters within the orbit of our protagonist-family are delineated with a cause of death and a date of death – is that it is also so full of life. You could argue that there are characters that take precedence over others, namely Bufty (the matriarch in everything but name), Irene (the tarot reading mystical great-grandmother), and Rita (the prodigal daughter who opens the novel), but Vincent never takes sides. It’s also very likely that you’ll walk away with your own favourites, or the ones that speak to who you are in your own family the most, but if your favourite characters are anything other than the twins-but-not-twins running the local pub, you’re sadly incorrect.

I’m an easy target for Hoods Landing. Towards the end of her life, my mother and her partner pulled up roots in Papakura and moved to Onewhero, a small town a few clicks in from Port Waikato, and out from Pukekohe. While the book isn’t explicitly set here, it might be set in the next, lightly fictionalised, town over. Every town you drive through is somebody’s home, and I feel so many of the realities of Onewhero and its surrounds captured perfectly here by Vincent. (Also, full disclosure: During my time at The Spinoff, I was delighted to commission Vincent, and we share a deep enthusiasm for movies and musicals older than us both. I’m both fan and friend for reasons that extend beyond our sensibilities.)

This part of New Zealand is its own ecosystem, although really every town, every village, every street is its own ecosystem if you zoom in close enough. Dollar stores, gas stations, pubs are their own landmarks, their own gathering points by virtue of there being nothing else. Even when you’re holding a grudge of 30 years against someone for a perceived slight, you still make them a casserole when you know they get sick.

Most crucially, Vincent doesn’t bring an outsider’s lens to this community. It would be so easy for this family to be rendered in the broad brushstrokes by someone who doesn’t stop on the drive between Papakura and Hamilton, but Vincent deeply understands the dynamics of a family that may have types, but those types exist because even families need to put their individual family members into boxes, just to get through the day. She pulls out layers from beneath the third generation especially, the aforementioned Rita, the many-husbanded Judy and the flighty Jayne, to reveal depths, and deep humour. Without ever feeling schematic or formulaic, every character gets their chance to show their humanity, their best side, and their not-so-good side. Just like every Christmas lunch,

The Gordons would perhaps not describe themselves as a happy family, and perhaps neither would those that orbit them. They have death, they have secrets, they have heartbreak. They certainly get on each other’s nerves. In that way, they feel as real as any family you might sit behind in Church on Christmas Eve, or see in the waiting room at a hospital. With Hoods Landing, Vincent has made The Gordons feel real, using all of the tools that only someone deeply skilled in the craft of fiction prose can do, and also with the bigness of heart and soul would ever want to.

Mortality is a pretty mortifying thing. We don’t want to think about dying, what happens when we die, and in a cruel irony, what happens if we don’t die. It doesn’t help that much of the art and media about ageing doesn’t exactly treat it as the most edifying of human processes. Life on a Loop, starring Ellie Smith in her first New Zealand stage show in well over a decade, takes a gentler view on the ageing process.

Life on a Loop is loosely framed, taking place in a rest home on Christmas Day. Through multiple characters, Smith traces a day, which is just like any other, and yet, still Christmas. It’s not the horror story of say, The Rule of Jenny Pen or Amour, but it’s not exactly a walk in the park. Still, Smith treats her subject matter, the home and its patients, with tremendous care. People can be infuriating, they can be funny, they can be terrified, no matter what age they are. (Unfortunately, pettiness is also part of the human condition from birth ‘til death, and possibly even beyond.)

Smith, who also wrote the show, is a magnetic presence. She brings old school theatre craft to Q’s Rangatira space, moving amongst her seven characters fluidly, with maximum charisma. The centre of all these characters is Grace, who marches through the rest home with a seemingly unbroken warmth and unwavering commitment to treating the patients in her care as people. While Smith makes a mark with all seven characters, it’s Grace that leaves the biggest mark; you can sense that her big smile comes from a mixture of practice, demeanour, and sheer force of will.

The show surrounding Smith is unobtrusive, more scaffolding than production. John Parker’s set looks authentically like what you might assume from a rest home; chairs that have been more than their fair share of occupants, and could be ecosystems in their own right. Peach’s direction has a similar light touch, providing gentle shifts in mood to allow Smith to move from character to character.

Sometimes, I found myself wishing that Life on a Loop was a little bit more of a commentary, or that it had a little bit more grit to it. But that’s simply not the show it is, and that’s fine; you don’t have to shake an audience by the shoulders to move them. Like the character at its centre, the point of the work is to show the humanity of these characters. These aren’t patients who were once people, they’re still people. The lives they have are not any less vibrant, or important, just because the time ahead of them is shorter than the time behind them. Life on a Loop is a gentle reminder of that, a warm tap on the shoulder.

Hoods Landing is available this week from Āporo Press. LIfe on a Loop plays until November 16 at Q Theatre.

Further Reading

- Over at The Spinoff, I wrote a preview of Woman Far Walking, and spoke to Witi Ihimaera and Miriama McDowell about what the show means 25 years on from its debut. The show runs at the ASB Waterfront Theatre until the end of next week.

- Also over at The Spinoff, I reviewed The Dry House, which is still playing at Basement Theatre this week.

- At The Big Idea, I wrote a feature on the mighty Prayas Theatre on its 20th year. The show it was tagged to has since closed, but Prayas Theatre never stays dark for very long.

Writing and reporting takes time, and if you want to support the amount of time it takes (and ensure that the scant amount of meaningful coverage of local art can continue), please considering supporting Dramatic Pause with a paid subscription ($8 p/m, $60 p/a) and if you can't afford a paid subscription, please share the work with your networks!

Member discussion