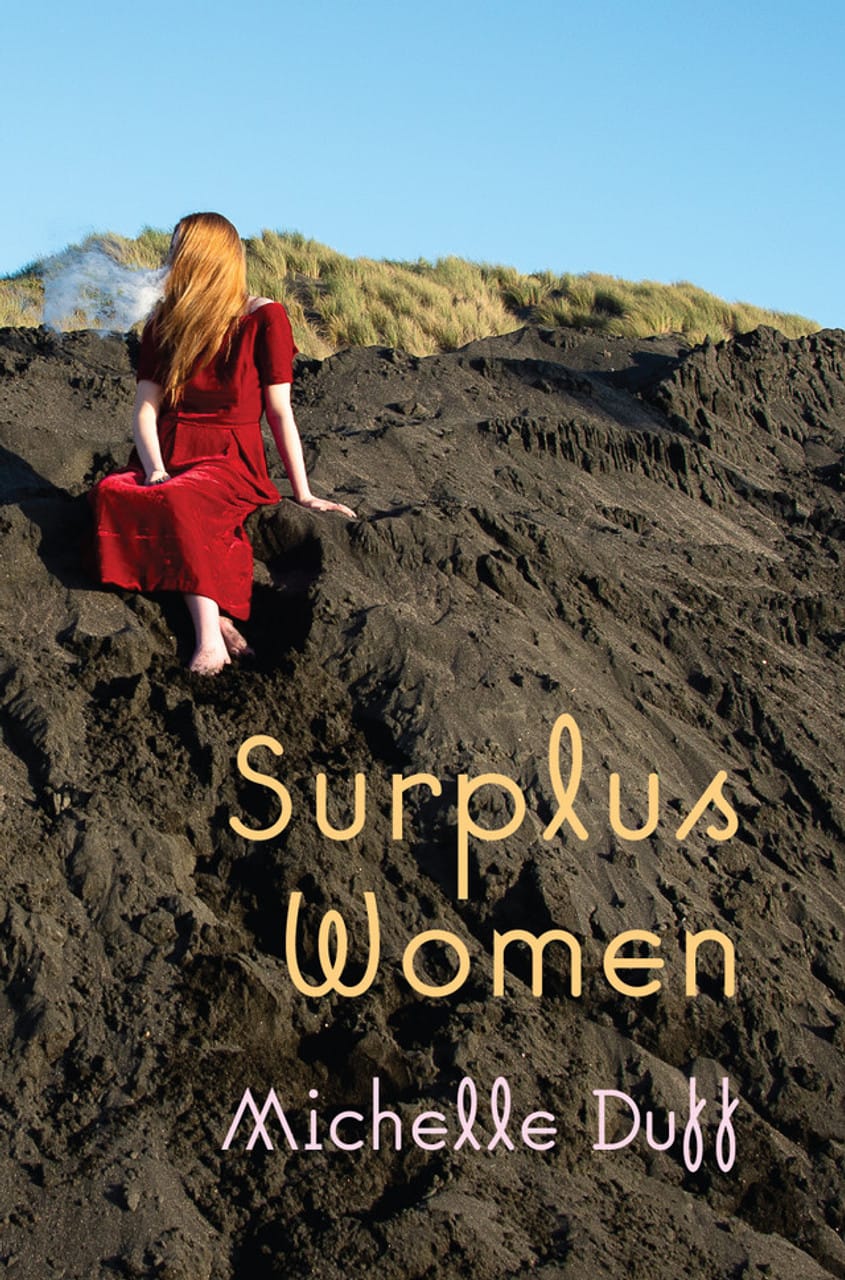

Critical Corner: Surplus Women

In this edition of Critical Corner, a review of Surplus Women, Michelle Duff’s debut collection of short stories.

A great short story is an algebraic equation. Every figure is exactly in place, it all makes sense, and it exists as its own self-contained creature. Within a few pages, a couple of thousand words, we get a life. We understand all the questions that a good journalist might ask – who, what, where, how, and most importantly why.

With her first short story collection, Michelle Duff, a journalist with more awards than many have bylines, presents stories about women in past, present and speculative Aotearoa, stories that “remind us of the sweet dreams we used to have and how it feels to wake up from them”.

The execution of Surplus Women however, is a scattershot barrage across those intentions.

Duff’s stories don’t adhere to any one genre or focus. Across the 15 stories, there are stories of teenage girls, stories of cops, even speculative fiction. While the collection draws its title from one the stories, “Surplus Women”, a key theme throughout is women who keep their words to themselves in the present, often to their own detriment.

The tone of the stories also varies. “Five times Roxanne has lied about her vagina: A non-comprehensive list” is as comedic as you assume it is, while “Your Loss” is one big middle finger delivered across eight pages and “Dreamscape” is a speculative take on forgetting a romance, with more of a wellness spin than an Eternal Sunshine one.

This scattered focus leads to the feeling that some stories might feel better lifted out of the context of the collection, to have the chance to stand on their own two feet rather than in relief to something else. “Gracie”, easily the most effective story, about a young girl in a less-than-ideal home situation continuing to muddle her way through, is nearly immediately displaced by the least plausible story, “Monstera”, whose protagonist is a Real Housewives satire that is neither accurate to that reality or funny enough to pass as parody. This protagonist, shared between the two stories, is a collection of caricatured bits that builds up an idea of a character, rather than the fully-formed protagonist of “Gracie”, who doesn’t know what she doesn’t know until she does.

Duff’s voice, in this debut collection, is unwavering and not always to the benefit of the stories themselves. While she has a good sense of narrative flow, her sentences often stand in the way of this flow. Passages like, “In class he was like this too, smart and funny, but in a way that teachers found endearing instead of insolent and that Lauren sometimes found intimating” and “The girl slept like a washing machine; no sooner had Irene become comfortable than Alexandra would be lumbering up the ladder, or flinging the blanket off her bunk into Irene’s face, where she would wake with a snort” are weighed down with so much information, without colour or clarity to buoy them.

It’s an eye for detail that is, perhaps unsurprisingly, journalistic, but detrimental to this particular form. Details are flooded unevenly through these stories, in a way that derails narrative momentum and is more distracting than it is informative. Take this sentence from the aforementioned “Monstera”:

“She offered the platters to Cyndi, who chose a smoked-salmon canape. Flo Rida came on the sound surround and a few of the younger agents started a dance floor in front of the burnt-amber velvet curtains down by the conversation pit.”

The detail is specific, but not rich. It’s the kind of detail a playwright would put in their script for the designer to take notes from, or a journalist would put into a profile that would then be illuminated by a photo. It’s not unrealistic for an author to expect a reader to do a little imagining themselves, but these details are often placed at moments when the given circumstances are so clear that they actually distract from the world Duff has created. (The most unfortunate example of this is a paragraph of biography in the title story that happens right at the climax; context when all the reader needs is information.)

Other times, Duff’s voice feels at odds with her characters. “I was pretty lit, which is always a great time to head to the club and see what the fuck is upppp” is something somebody who used to go to clubs might say, rather than an uttering from that character themselves. In a collection that seems so intent on getting inside the heads of various characters, Duff instead sits behind them and describes what is happening, only occasionally delving deep within their inner life. Again, it’s telling that the story that feels most authentic and full of life – “Toxic”, about a journalist blowing up her own life – is the one where actions tell the stories, not thoughts and intentions.

Another consistency of Surplus Women is the tendency for a rug-pulling twist. While the nature of the twists change – some are twists based on withholding evidence from the reader, others a jump in time after a life-changing event – they more often than not happen in the last few pages. These twists often contain the theme of the story, a weighty reminder that these stories, these characters, are about something, rather than just being in their own right. It’s not that these aren’t important messages but short story is not a form that is generous to the delivery of theme over the package of that same theme. These packages and their structures are too familiar, especially when placed next to each other.

Again, a great short story is an algebraic equation. It feels effortless. The numbers are in place. You can look at it and know it makes sense. The algebra of Surplus Women is unfortunately off. The sentences and the details pile up without adding up. Characters that start off as people end up being vessels for themes. Even the mathematician doesn’t seem quite attuned to the form.

Surplus Women is available now from Te Herenga Waka University Press.

Writing and reporting takes time, and if you want to support the amount of time it takes (and ensure that the scant amount of meaningful coverage of local art can continue), please considering supporting Dramatic Pause with a paid subscription ($8 p/m, $60 p/a) and if you can't afford a paid subscription, please share the work with your networks!

Member discussion