Revisiting Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas 20 years later

I woke up last Saturday morning extremely ill after a week of nine-to-nine days, many of which involved hearing my own words spoken back at me in an audience. This is not a relatable human experience.

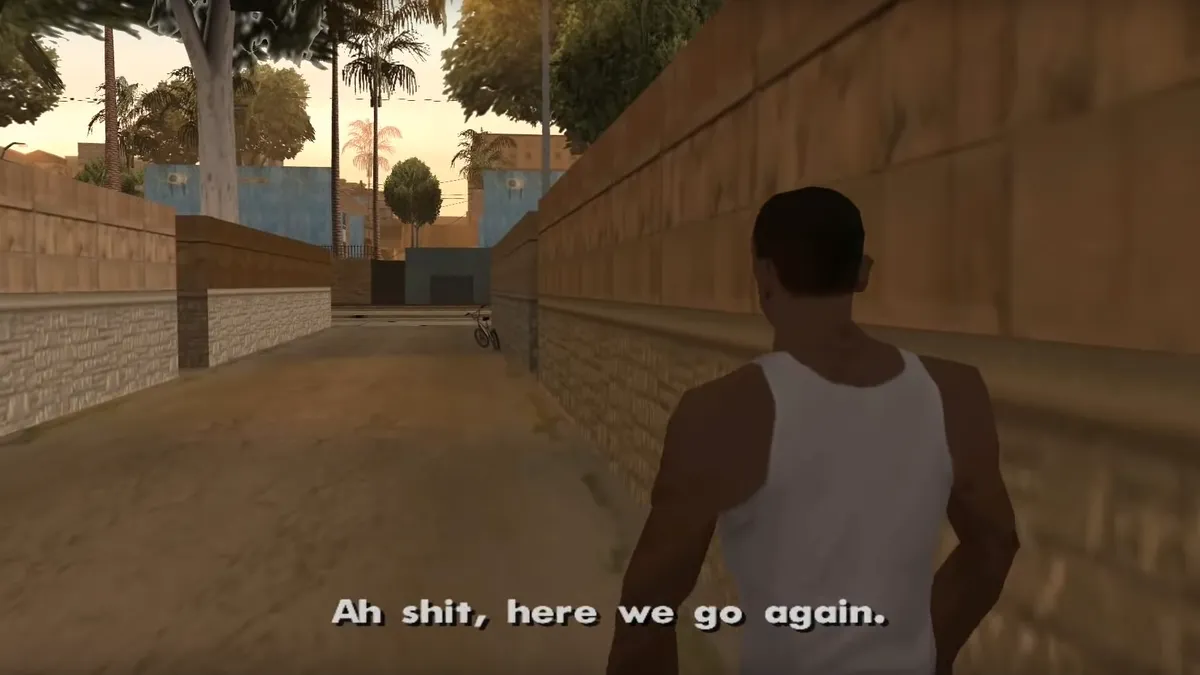

More relatable, perhaps, is the experience of playing Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas back when it came out in 2004. Like many a millennial who was not old enough to legally play it – when the R18 rating actually mattered, before broadband internet and phones with said internet on it – I spent dozens of hours in the unprecedented huge open world of San Andreas, made up of fictionalised versions of Los Angeles, San Francisco and Las Vegas. Even more unprecedented was the freedom, the amount of stuff there was to do. It didn’t matter that not necessarily all of it was fun – the mere mention of the fucking flying school will send anybody who has played this game into hives – just that the scale was there.

Statistically, a lot of people have played Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. Not only is it the best selling game on the best selling console of all time (PS2, represent), it’s been available pretty much consistently since it was released, having been remastered and then released in a “definitive” (honestly fairly crap and deservedly criticised) edition in 2021. One of my core gaming memories is marching on down to United Video with my mother to hire it out for three days – for $12, thank you very much – to try to make my way through it.

How does it hold up twenty years on? Would the gameplay stack up? Would the humour stack up? Would I be able to make it through any mission requiring the truly ludicrous flying controls?

I’m gonna be up front with the most jarring thing about playing this game 20 years on: The racial politics. Because, woof, does this game – especially the first act, set in the rougher part of Los Santos – feel like the product of a bunch of white people in Scotland. As a fourteen year old, I was not fully across the authentic experience of a Black person in Los Angeles, and I don’t think the people who wrote this game were either. (I don’t think any person on that side of the Atlantic has ever uttered the phrase “big willy”, you guys.)

Once you can get past that – if you can get past it, and sometimes getting past is putting on a podcast and ignoring the cutscenes – I was struck by how of a time San Andreas feels now. It marks, I feel, the turning point from triple-A games being allowed to be silly and janky, to having to be taken serious. You only have to look at the serious (and not especially great) storylines to all of Rockstar’s games since then to see that their sense of humour was thrown aside in favour of being taken seriously.

Neither of the Grand Theft Autos that followed San Andreas are bad games, but they are damn dour ones. They’re also not amazingly memorable ones. My prevailing memory of Grand Theft Auto IV is someone with an Eastern European accent screaming, “Roman!” My prevailing memory of Grand Theft Auto V, which admittedly tried to swing a bit back towards the series’ satirical roots, is the game’s naked desire to be Breaking Bad without any of what made Breaking Bad actually great. (I daren’t approach either of the Red Deads, great games with nary a smile cracked between them.)

Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas is a game that laughs more than it cries. This was where gaming was at, at the time. People didn’t take the artform seriously, and we were a good decade ahead of ludonarrative discourse and how it applied to open world games where your protagonist is allowed to discriminately murder with zero permanent consequences. Which isn’t to say that there aren’t intense moments in the game – betrayals, people yelling at each other, meaningful character deaths – but they’re scarce between silly dick jokes.

The other thing that was so pleasing to revisit all these years later is the player’s agency within the missions. This is an era where games, even games of this scale, wanted you to break them and test them. One mission late in the game is trivialised by simply shooting out your enemy’s tires, which is not encouraged but is sure as hell allowed.

When you compare that to recent triple-A games which are so clogged with content that the developers want you to engage with in one specific way, it’s refreshing. Even Assassin’s Creed, a series which used to be lauded for how it gave players inventive ways to approach its assassinations, ended up abandoning that in favour of rigid mission design (and then abandoned that in favour of, well, barely any mission design, which is not better).

I don’t hate these games. When it’s done well, as in the Spider-Man series, it’s really great. There is a comfort in being guided through a well-designed mission by a team of developers who know what the hell they’re doing. It also does often feel less like a game and more like an interactive film. There’s very little agency here, very little of the gamer’s creative brain engaged.

Compare that to Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (and many other open world games of its era). An entire mission has a part that can be skipped if you simply choose not to follow your intended target across the water and participate in a protracted boat chase with terrible controls but instead snipe them from a distance instead. The rush of getting one “over” on the developers with a bit of common sense and creative thinking is a rare one nowadays.

As gaming as a form marches on forward, it’s easy to forget what’s been lost. As graphics get ever boringly closer to hyperrealism, we lose a great deal of imaginativeness. The more we treat games seriously, the more we lose a bit of their silliness. For a few hours, it was nice to go back to an era where even the most prestigious of games could be a little bit janky.

Writing and reporting takes time, and if you want to support the amount of time it takes (and ensure that the scant amount of meaningful coverage of local art can continue), please considering supporting Dramatic Pause with a paid subscription ($8 p/m, $60 p/a) and if you can't afford a paid subscription, please share the work with your networks!

Member discussion